How Africa's Geography Has Shaped Its History and Future

Deserts, rivers, coasts, and disease once isolated; now technology, infrastructure, and innovation are turning those barriers into bridges.

Isolation and Opportunity: How Africa’s Landscapes Shaped Its Destiny

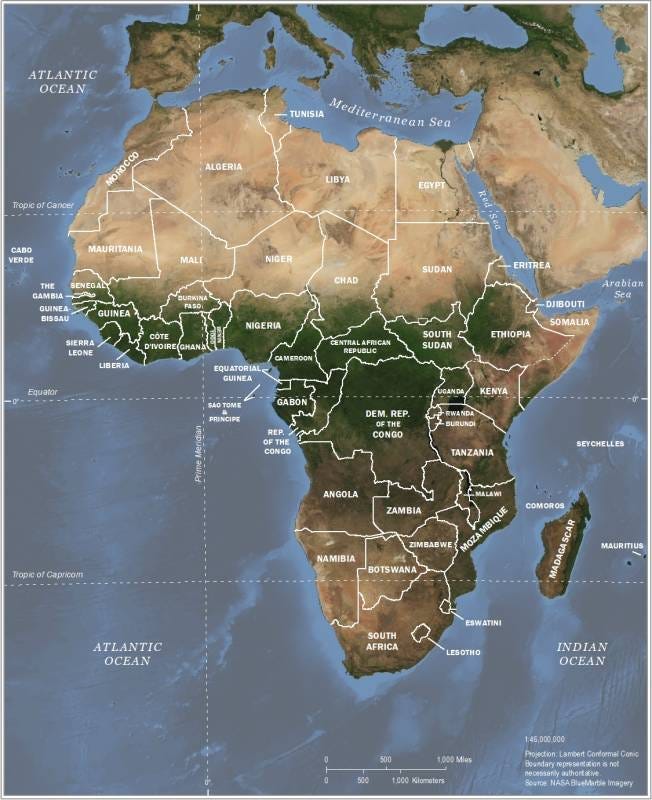

What if a continent’s shape could influence the fate of its people? As global power realigns and new corridors open across the world, that question isn’t theoretical — it’s urgent. Africa holds nearly 30% of the world’s mineral reserves, yet geography has long limited trade routes and connections.

Thomas Sowell puts it plainly in Wealth, Poverty and Politics: “interactions of various geographic factors with each other with non-geographic factors, including changing levels of human knowledge over time, make outcomes very different from what they would be if determined solely by a given geographic factor or even by geographic factors as a whole.” His point reminds us that deserts, coasts, and rivers weren’t fixed barriers. They changed as human knowledge, technology, and relationships changed.

For generations, geography shaped who prospered. Africa — resource-rich, culturally diverse, and the place where humanity began — was often separated by its own natural walls. Those deserts, jungles, and mountain ranges slowed exchange and hid much of its potential from the outside world. Today the question is whether the 21st century can turn those former barriers into bridges — and how that shift could reshape Africa’s future and the world’s.

From the Sahara Desert’s vast expanse of sand dividing north from south to rainforests that bred malaria and sleeping sickness, Africa’s landscapes have long been formidable.

Along the coasts, treacherous waters claimed ships at the Cape of Good Hope — the so-called “Graveyard of Ships”.

Africa’s great rivers—the Nile, Congo, and Zambezi—broke into rapids and cataracts as they neared the sea, cutting off travel and trade. While Eurasia’s east–west corridors let crops, animals, and ideas move easily through similar climates, Africa’s north–south axis pushed them apart. Geography built walls around Africa’s potential, and knowledge often stopped at the edge of those barriers.

How the Nile Shaped Egypt’s Strengths — and Its Limits

I first glimpsed Africa’s geography not in a classroom, but as a boy sailing a felucca on the Nile in the early 1990s. From the boat, the contrast was stark: desert on one side, a narrow fertile green valley on the other. Villages hugged the river, their fields fed by canals that turned dry soil into abundance. The Nile was not just water — it was life, sustaining dense populations in a valley often only ten to twenty miles wide.

Yet even this life-giving artery was bounded by barriers. My family’s journey ended before Aswan, where we left the boat and continued south by car. The reason, I later realized, was geography itself. Cataracts — rocky rapids and shallows — broke the river into segments, blocking continuous navigation. What seemed a single blue line on the map was in reality a guarded corridor, bounded by cliffs and desert.

Geographer Halford Mackinder observed Egypt was a civilization “from desert edge to desert edge,” a fertile valley defended by walls of rock on both sides. Geography had the final word — providing stability inside the valley but exposing Egypt whenever outsiders reached the delta. Invaders rarely came from east or west; the southern route into Sudan was narrow and controllable. Egypt’s weak point was always its delta — the open plain where Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and later Europeans advanced. Geography gave Egypt security and fertility but also confined it within narrow borders. The Nile was both blessing and limit — a reminder that even the greatest resources carry constraints.

Why Africa’s Natural Barriers Slowed Connection and Growth

To grasp these challenges, it helps to think like a geostrategist. Halford Mackinder’s “Heartland Theory” pictured the world as a chessboard, where power flowed from controlling key geographical pivots. In this grand game, much of Africa lay at the periphery, its internal complexity muted by external barriers.

As Tim Marshall notes in Prisoners of Geography, these barriers shaped Africa with chilling clarity:

The Treacherous Coast: Africa has a surprisingly short coastline for its size, with few deep-water natural harbors. Rivers like the Congo and Niger explode into waterfalls and rapids just as they near the ocean, preventing ships from sailing inland. This turned the interior into an isolated island.

Gurara Falls is beautiful for tourism but for navigation it has always been an obstacle.

The Disease-Ridden Interior: The prevalence of malaria and trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness, carried by the tsetse fly) made settled agriculture and the use of draft animals incredibly difficult, crippling agricultural productivity for centuries.

The Impenetrable Barriers: The Sahara Desert is an ocean of sand separating Sub-Saharan Africa from Europe and the Middle East. The Congo Rainforest is a dense, wet fortress. These features prevented the easy diffusion of technologies and ideas that flowed so freely across Eurasia.

Culture and craft also highlight the gap. Many European advances — paper, printing, gunpowder, the compass, rudders, even Arabic numerals — originated elsewhere. Imagine how different Europe’s trajectory would have been without this transfer of knowledge. By contrast, “Fortress Africa,” with its Sahara and escarpments, restricted such exchanges, leaving much potential locked away.

Agriculture faced further limits. Tropical soils generally yield less than temperate ones, as Uzo Mokwunye observes. Thomas Sowell makes a similar point in Wealth, Poverty and Politics: regions with fragile soils faced greater barriers to producing the surpluses needed to sustain urban growth and technological advance. Yet there were exceptions: along the Nile, annual floods renewed nutrients, sustaining farming for millennia.

Even where rivers existed, minimum depth mattered more than averages. The Nile, for instance, could not carry Rome’s largest warships. Egypt’s vulnerability was always in the delta, open to sea power. Lacking quality timber for shipbuilding, Egypt often had to hire others to build its fleets. Long before Europeans, Pharaohs even envisioned a canal linking the Red Sea to the Mediterranean via the Nile. Elsewhere, rivers like the Niger were only seasonally navigable, limiting trade and economic development.

As David S. Landes observed in The Wealth and Poverty of Nations, Africa is more than twice the size of Europe, yet its coastline is shorter — a paradox that limited harbors and inward penetration. Geography is not egalitarian; some nations are more geographically fortunate than others. Mountains and steppes each bring trade-offs, shaping economies as well as defense. Geography influences outcomes, but it is not destiny — there is no strict determinism.

How Africa’s Geography Still Shapes Its Present Challenges

History left scars as deep as shipwrecks at the Cape of Good Hope. The name itself was a euphemism — for sailors, it was less a Cape of Good Hope than a Cape of Death. Storms, rocky shoals, and hidden reefs made survival a gamble. Beneath the waves lurked yet another danger: the Great White shark, apex predator of these waters.

Such perils remind us that Africa’s obstacles were not only on land but also under the waves, shaping who survived and what possibilities were lost.

This is more than history. As Thomas Sowell reminds us, difficult starting conditions shape long-run outcomes — but they do not predetermine them. Africa, with immense mineral wealth and human capital, was systematically disadvantaged by geography, and later by artificial colonial borders.

The implications are profound. We cannot understand modern Africa’s challenges — from infrastructure gaps to political instability — without first understanding this geographic inheritance. It is not about a deficit of culture or capability, but a story of profoundly difficult starting conditions. And that raises the question that matters most: what does this mean for us — and for the generations that follow? Whether we treat geography as a permanent prison or as a challenge to be mastered will determine not only Africa’s trajectory, but the stability, trade, and resilience of the world our children inherit.

This is the reality that must be accepted. As the ancient philosopher Lao Tzu observed, “Act by not acting; do by not doing. This is the way of nature.” For Africa, this means the first step is to stop fighting a geography that cannot be changed and to start understanding it, accepting its constraints, and building with what is there. This is Africa’s Tao Te Ching — its fundamental path to power. The realization is that no one will come to build it for them; the future must be built from within.

From Barriers to Bridges: How Africa Is Rewriting Its Geographic Story

Africa’s history shows that geography has never been neutral. It either isolates or enables. The lesson for today is clear: geography still shapes choices — but now those choices are conscious, not imposed.

Nelson Mandela once said, “It always seems impossible until it is done.” The impossibility was geography itself; the doing is using modern knowledge to overcome it.

If deserts once divided, new rail lines can connect regions together. If rivers once blocked, energy and transport corridors can transform them into engines of growth. For citizens, this means recognizing that prosperity depends on building with geography, not against it. For policymakers, it means investing in ports, rail, and health systems that convert inherited obstacles into opportunities. For global partners, it means seeing Africa not as a place of limits but as a cornerstone of shared resilience and growth.

As Thomas Sowell observed, difficult starting conditions shape outcomes, but they do not dictate destiny. Geography still sets boundaries — the Sahara will remain vast, the Congo dense, the Cape of Good Hope perilous. Resilience will never mean conquering these realities, but bending with them — using foresight and courage to turn walls into pathways.

And that is where the lion belongs. The lion is not the largest, fastest, or smartest animal, but it rules because of its mindset. That same courage and focus mirror Africa’s challenge today: true power lies not in geography alone, but from the will to turn barriers into bridges. That is the path forward, not only for Africa, but for the generations who will live in a world shaped by its rise.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. It empowers readers with objective geographic and planning insights to encourage informed discussion on global and regional issues.