Las Vegas and the Southwest’s Water Reckoning: Scarcity, Strategy, and Resilience

Las Vegas faces water and energy limits, but smart planning, native landscapes, and interstate cooperation offer a path to resilience in the Southwest.

A Hostile Landscape

Beyond the glittering lights of Las Vegas lies a sobering truth: the Mojave Desert is not just dry — it is one of the most water-scarce regions on Earth. With an average annual rainfall of just 4.18 inches (NOAA, 1991–2020), the region cannot support agriculture without irrigation. Every crop, every drop of drinking water, and every golf course oasis depends on the Colorado River — a lifeline now under unprecedented strain.

The Colorado River: A Lifeline

There would simply be no Las Vegas without the water provided by the Colorado River, which originates all the way from the high Rocky Mountain in Colorado with many significant tributaries from Wyoming, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. Unfortunately, the Colorado River watershed has been receiving less snowfall, which is now creating a crisis for the South West region.

According to the United States Bureau of Reclamation (USBR), the construction of the Hoover Dam started on April 20, 1931, and all the features of the dam were completed on March 1, 1936.

The Hoover Dam created Lake Mead, a manmade reservoir that transformed water management in the Southwest. In addition to providing water to Las Vegas, the Colorado River also produces electricity via the Hoover Dam. According to USBR, the Hoover Dam produces 4 billion kilowatt-hours of hydroelectricity each year, which is enough to serve 1.3 million people.

Hoover Dam: Power and Peril

The Hoover Dam operates most efficiently when Lake Mead’s elevation is above 1,050 feet. Below this point, energy output drops. If levels fall to 950 feet, power generation would halt altogether. The “dead pool” — the point at which no water can flow downstream — is 895 feet (National Park Services,).

Water delivery is even more delicate. Las Vegas originally drew water from Intake Pipe #1 (above 1,050 feet), which ceased functioning in 2022. Intake #2, built in 2000, sits at 1,000 feet. The real game-changer, however, is Intake Pipe №3, completed in April 2020 at an elevation of 860 feet. Positioned well below the dead pool threshold of 895 feet, it can draw water even if Lake Mead falls drastically — or if Hoover Dam were rendered inoperable. In effect, this intake allows Las Vegas to access water from near the natural riverbed. As long as the Colorado River continues to flow, even minimally, this intake secures the city’s survival. Much like Cairo’s reliance on the Nile, Las Vegas’s future is anchored to the enduring flow of a single river — and its ability to tap it even in crisis.

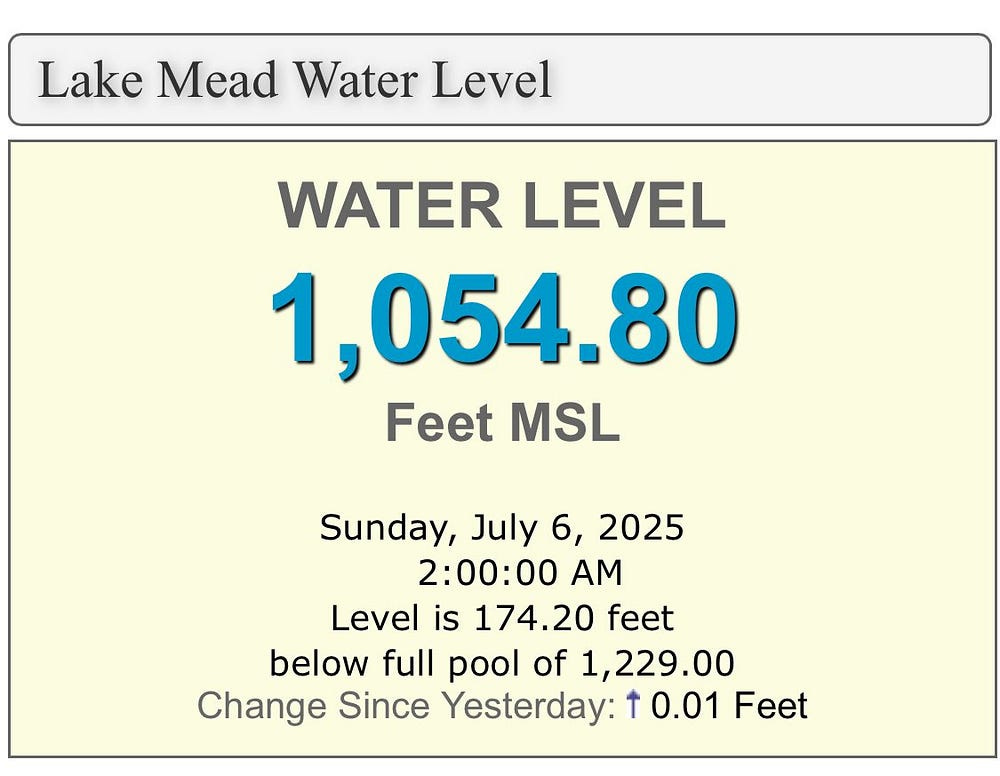

In July 2022, Lake Mead hit a historic low of 1,040.92 feet, triggering alarms across the Southwest. That elevation rendered Intake #1 useless and brought Intake #2 dangerously close to failure. As of July 6, 2025, levels have slightly recovered to 1,054.80 feet, but the long-term trend remains dire.

Energy Outlook

Electricity generated by Hoover Dam is divided among the lower basin states:

California: 55.92%

Nevada: 25.13%

Arizona: 18.95% (USBR)

This power-sharing arrangement means all three states are deeply invested in the reservoir’s stability.

If Lake Mead were to drop 30 feet annually, power generation could cease in as little as three years.

Water Supply and the Bigger Fight

The water situation is far more critical. Nevada only receives 4% of the Colorado River’s water allocation under the Boulder Canyon Project Act, compared to 58.67% for California and 37.33% for Arizona. While Las Vegas has become a model of water efficiency — banning ornamental lawns and investing in reuse technology — the city remains reliant on political agreements and infrastructure maintenance.

However, it’s unlikely to go completely dry, thanks to ongoing flow from the Upper Basin. The real issue will be interstate water negotiations and managing demand from agriculture-heavy regions like California’s Imperial Valley and Arizona’s Yuma region.

Final Thought: A Living Legacy of Resilience

While Las Vegas faces real challenges, it is also one of the best-positioned cities to adapt. Its aggressive water conservation programs and deep intake infrastructure give it a strategic advantage. The same cannot be said for large-scale agriculture in California and Arizona, which could face collapse under severe drought scenarios.

The Southwest’s survival hinges not just on infrastructure but on cooperation, resilience, and policy innovation. For decades, cities like Las Vegas have relied on blue infrastructure — dams, pipelines, and reservoirs — to make desert life possible. But now, cities, farms, and entire states must adapt to a future where water is more scarce and climate volatility is the norm. The desert teaches us that survival isn’t about fighting nature, but harmonizing with it. Las Vegas was once dismissed as an unsustainable fantasy. Like Cairo and the Nile, Las Vegas and the Colorado River are inseparable. Each shows how geography doesn’t doom a city — it defines the strategy needed to endure. With ingenuity, conservation, and cooperation, Las Vegas could now become a model for how cities survive and thrive in a drier, hotter world.

While engineered solutions will play a major role, they alone aren’t enough. To build long-term resilience, we must also rethink our relationship with the land itself. Green infrastructure — nature-based systems like native vegetation, tree cover, and soil restoration — can complement pipes and pumps by working with the landscape to retain moisture, reduce heat, and slow desertification.

We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Strategies like mass plantings of native trees — such as the drought-proof nut pine (Pinus edulis) and ironwood — could transform degraded lands:

Thrives on 12" annual rainfall (less than half what crops require)

Deep roots stabilize soil, combat desertification, and trap moisture

Produces nutrient-dense pine nuts, offering food security and economic potential

Imagine “green corridors” stretching from the Colorado Plateau to Arizona: natural windbreaks that cool microclimates, restore biodiversity, and sequester carbon. In a time of crisis, these quiet engineers of resilience remind us that the best solutions often grow from the land itself.

Las Vegas’s survival hinges not just on pipes and policies, but on thinking like a nut pine — rooted, adaptable, and life-sustaining against all odds.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. This blog aims to educate and empower readers through objective geographic and planning insights, fostering informed discussion on global and regional issues.