Savannah's 1733 Plan: A Blueprint for Resilient Cities

Designed before cars or air-conditioning, Savannah's city plan shows how geography, shade, and fairness built one of America's most livable cities.

What We Can Learn from a 300-Year-Old City

I have visited Savannah in both summer and winter, and each time I am struck by how naturally it invites you to walk. The streets breathe at a human pace — shaded, calm, and welcoming — reminding me what so many modern subdivisions have lost: the simple pleasure of moving through a place designed for people, not traffic. This isn’t a futuristic vision — it’s Savannah, Georgia, whose revolutionary plan was drawn in 1733 by General James Oglethorpe.

General James Oglethorpe’s plan for Savannah was a radical departure from the cramped, chaotic cities of his time. It was both a social and environmental experiment, built on the belief that design could shape fairness, health, and community. Today, as communities struggle with suburban sprawl and neighborhoods where people seldom know one another, his vision offers a powerful, timeless lesson. Here are the key things you need to know to understand the significance of one America’s best-planned city.

How Savannah’s Squares Create a Perfect Neighborhood

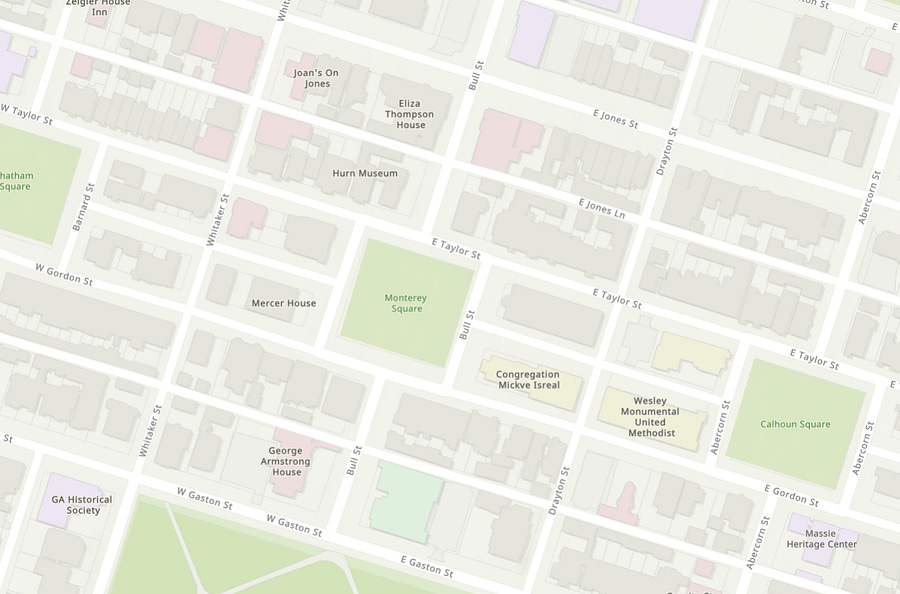

Oglethorpe’s genius lay in a simple, repeatable module called the “ward.” Each approximately 12-acre ward was centered on a public square, which served as its civic heart. The four corners of the ward contained four “tythings,” each consisting of ten equal-sized house lots (60 by 90 feet) for private homes according to NPS. While the 60-foot-wide lot was the standard, these were sometimes subdivided into increments of 20 or 30 feet, creating a diverse pattern of building sizes and types. This layout ensured every resident lived just steps from the shared public square.

Flanking each square on the east and west were larger Trustee Lots, reserved for civic and institutional uses such as churches, markets, or meeting halls. This simple pattern produced a vibrant mix of homes, commerce, and public life within a few blocks. The squares were not decorative extras — they were the community’s shared backyard and gathering place, spaces where daily life unfolded in the open

Many of Savannah’s original ward patterns still exist today. Though some blocks near the urban core have been combined into larger parcels, Oglethorpe’s framework — his rhythm of squares, streets, and small lots — remains strikingly intact. It was placemaking before the term existed — a pattern built to grow incrementally, repeatable block by block, which is why it still works today. As Charles Marohn of Strong Towns notes, cities historically evolved through small, flexible steps, and Savannah’s design reflects that truth: a structure adaptable enough to evolve rather than break.

The Simple Reason Savannah Stays So Cool and Walkable

Savannah’s hot, humid climate demanded more than beauty — it required foresight. Oglethorpe’s true genius lay in choosing a location designed for resilience. He placed the city atop a high bluff, about 40 feet above the Savannah River — a decision that proved both healthful and protective. Elevated above the swampy air of the 18th century and beyond the reach of floods, the site gave Savannah a natural advantage.

The plan itself built on those strengths. Walking those streets in the summer, I felt the temperature drop the moment I stepped beneath the oaks. The difference isn’t subtle — it’s the kind of cooling that makes you realize design and comfort once went hand in hand. Centuries before “climate-responsive design” had a name, Savannah embodied it — proving that good planning begins with geography.

Savannah’s climate is hot and humid, but Oglethorpe’s plan created a natural cooling system long before air conditioning. He chose a high bluff 40 feet above the river, sheltered by vast pine forests from southern winds, for its healthfulness. By placing the city on a high bluff and working with prevailing winds and forest cover, Oglethorpe showed that resilience begins with geography. The plan amplified natural advantages rather than fighting against them — a lesson just as urgent for cities facing today’s heat and flooding risks.

Three centuries later, FEMA’s flood maps affirm Oglethorpe’s foresight. Savannah’s historic core still sits safely above the 1% annual-chance flood zone — proof that working with geography, rather than against it, remains the strongest foundation for resilience.

That same wisdom shaped the city’s architecture. Savannah’s early homes were designed for comfort in a warm, humid climate long before air conditioning existed: tall ceilings let hot air rise, and deep, shaded porches caught river breezes to create cool outdoor living spaces. More than decorative, these porches embodied vernacular resilience — inviting daily life outdoors and connecting neighbors through the gentle rhythm of shade, air, and conversation.

The enormous canopy of live oaks provides essential shade, softening Savannah’s summer heat and reducing the urban heat island effect common in modern concrete landscapes. The open pattern of squares and streets allows air to circulate freely, creating cooler, more comfortable microclimates — a masterclass in sustainable, climate-responsive design.

The Forgotten Fairness in Savannah’s Original Design

Oglethorpe was doing more than laying out streets and squares — he was designing a vision of fairness. The original Trustees’ rules banned slavery, limited land ownership to prevent aristocracy, and even prohibited rum and lawyers in an effort to maintain order and equality. Georgia was, remarkably, the only North American colony to prohibit slavery at its founding, a policy Oglethorpe defended as both moral and practical. According to historian Nancy Spannaus in Investigating American Slavery: The Case of Georgia, he viewed slavery as “against the very principles by which we associated together,” a direct challenge to the culture of the surrounding South. Though history later took darker turns, those founding ideals were built into the city’s very fabric.

But those ideals soon collided with the culture of the surrounding South, where plantation wealth depended on enslaved labor. Within a generation, the bans were overturned. By 1750, slavery was legal in Georgia, and the colony’s economy had aligned with its neighbors. Yet Savannah’s plan remained a physical echo of Oglethorpe’s early ideals — a grid meant to embody fairness, balance, and access for all, even as society moved in the opposite direction.

The equal-sized house lots and shared squares gave physical form to a belief that community could be planned as deliberately as streets. It’s a reminder that city planning is never neutral — it either reinforces inequality or helps build belonging.

Savannah’s history ultimately diverged from its utopian ideals. Slavery and inequality became woven into its story, proving that even the most thoughtful design cannot protect a community from the forces of its time. Yet the plan itself continued to point toward another way — one rooted in balance, access, and shared space.

The One Question Savannah Leaves Us With

Every time I return, I am reminded that Savannah’s appeal is more than nostalgia — it’s the richness of its design. The streets evolve, the buildings change, yet the underlying pattern still works. What makes Savannah especially captivating is its organic built environment: a tapestry of homes and styles that grew together over time. Within a few blocks, you can find single-family houses, duplexes, townhomes, row houses, and cottages — each distinct, yet part of a harmonious whole. That variety creates visual depth and human scale, a far cry from today’s uniform subdivisions. It proves that timeless design has nothing to do with age and everything to do with intent.

Savannah reminds us that the most resilient, livable communities are built on a human scale, shaped in harmony with nature, and grounded in shared space rather than private isolation. The question it leaves us with is simple yet profound: if we already have a 300-year-old blueprint for beautiful, walkable, and resilient neighborhoods, why do we so often build the opposite?

Savannah endures as both a lesson and a challenge — to imagine a future that respects geography, works with nature, and restores the human connection at the heart of every lasting community.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. It empowers readers with objective geographic and planning insights to encourage informed discussion on global and regional issues.

As always, very interesting!