The North Rim Grand Canyon: What It Reveals about Fire, Drought, and Resilience

Beyond the Flames: The Dragon Bravo Fire and the Search for Resilience

Why This Fire Matters

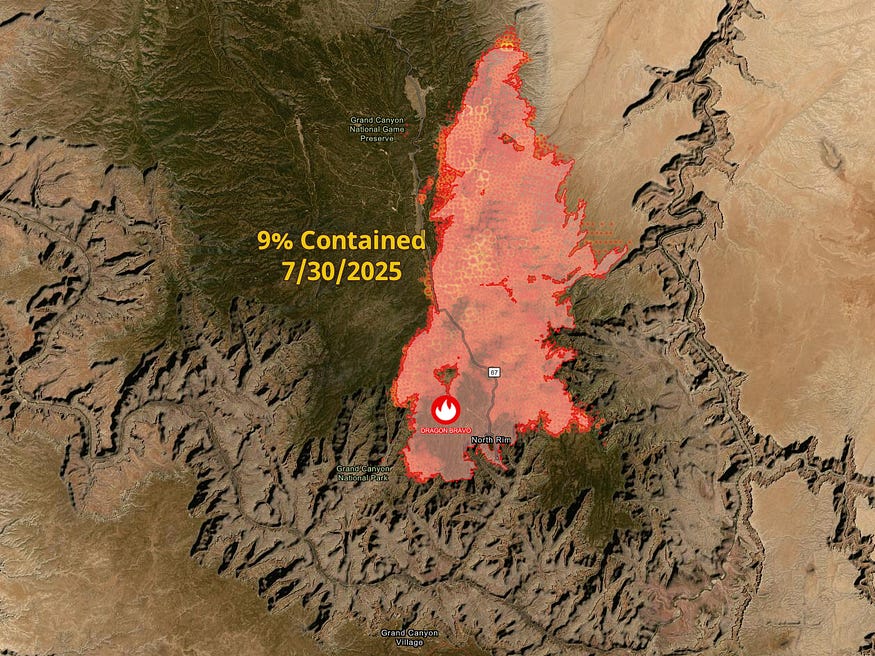

In July 2025, a wildfire sparked by a lightning strike began spreading across the Grand Canyon’s North Rim — one of the most iconic landscapes in the American West. The Dragon Bravo Fire burned approximately 85,682 acres (134 square miles) as of July 30, 2025 — nearly matching Las Vegas’ city limits (135 square miles), per the Esri US Wildfire Activity Web Map.

It wasn’t the largest wildfire on record, nor the deadliest. But it exposed a deeper challenge: our evolving fire policies are being overtaken by a climate growing more extreme. What began as a managed ecological fire spiraled into a costly and symbolic loss.

As droughts deepen and fire seasons intensify across the West, the question isn’t whether fire belongs in our ecosystems — it’s how we manage it, adapt to it, and learn from it.

A National Treasure at Risk

In Winter 2020, I visited the Grand Canyon’s South Rim with my family. As we drove north, the landscape shifted — from dry desert to grassy plains to forests of ponderosa pine. Just past the park gate, deer greeted us. I remember reading about the North Rim — higher in elevation, richer in trees, colder in winter. It seemed almost mythical in its beauty. Luckily for my family we arrived early enough in the park to see the Grand Canyon prior to a snow falling on the Grand Canyon. By the time we left you could not even the see the Grand Canyon.

Now, that landscape has changed.

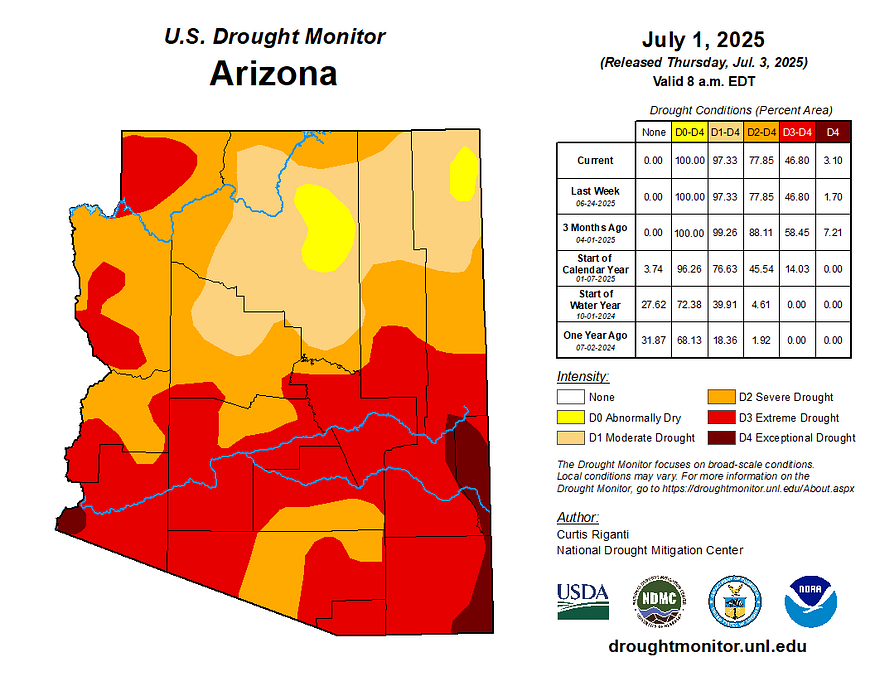

The Dragon Bravo Fire ignited on July 4, 2025, sparked by lightning on the Kaibab Plateau. Drought not only dries out the land — it reshapes weather patterns. During extended dry spells, the atmosphere can become unstable, triggering thunderstorms that deliver lightning without rain, known as dry lightning. These storms are especially dangerous in parched ecosystems like the Kaibab Plateau. While they may seem like relief, they often become ignition sources. In this case, the same drought that weakened vegetation also increased the chance of lightning strikes sparking fire, showing how multiple climate stressors can converge. Initially managed under a “confine and contain” strategy — a widely used ecological fire policy to reduce fuel buildup — the fire was allowed to burn within planned boundaries.

But by July 11, drought-dried vegetation, strong winds, and low humidity overpowered the strategy. According to the US Drought Monitor, the Grand Canyon area was under a Moderate Drought conditions. Some damage to crops or pastures; streams, reservoirs, or wells low; some water shortages

developing or imminent; voluntary water use restrictions requested.

Despite a shift to full suppression, the fire breached containment lines and destroyed more than 100 structures — including the historic North Rim lodge. Among the losses was the historic Grand Canyon Lodge on the North Rim — a cherished landmark built in the 1920s that had welcomed generations of travelers. Its destruction is more than structural; it marks the erosion of shared memory, heritage, and the spaces that connect people to place.

How we approach fire management reminded me of how floodplain management has evolved. The original National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) of 1968 focused on levees and elevation to make areas reasonably safe from flooding — a FEMA term that still guides land use decisions today. But as risk outpaced infrastructure, FEMA shifted toward non-structural approaches like open space and higher building standards through the Community Rating System (CRS). We began embracing resilience over resistance.

Wildfire policy is evolving. After decades of widespread suppression, many fire agencies are incorporating approaches like prescribed burns, strategic fuel management, and Indigenous fire stewardship. Resources such as the 2006 Tribal Wildfire Resource Guide highlight traditional Native practices of seasonal burning — once overlooked in mainstream policy, now increasingly acknowledged as valuable contributions to fire resilience.

While this piece doesn’t explore Tribal fire stewardship in depth, it may be worth learning more about Indigenous leadership in wildfire resilience. What’s increasingly evident is that long-term success depends on integrating scientific insight, cultural knowledge, and adaptive planning.

Fire’s Ripple Effect: Threatening the Colorado River’s Future

This fire isn’t just about fire. It’s about water.

The North Rim feeds the Colorado River watershed — the same river that sustains 40 million people across the Southwest. Ash from the fire could enter tributaries and affect downstream water quality. And as winter approaches, a scorched forest canopy may reduce snowpack retention and delay spring melt — compounding stress on Lake Mead.

As I wrote in Las Vegas and the Southwest’s Water Reckoning, Lake Mead is already near historic lows, straining both water supply and hydroelectric power for Nevada, Arizona, and California. The Grand Canyon and its forests play a quiet, critical role in that water system — regulating snowmelt, filtering runoff, and anchoring the region’s natural water infrastructure.

Wildfire and drought are no longer isolated events. They are converging.

The Resilience Blueprint: Lessons from Floods and Fires

Like flood policy, fire strategy has followed a familiar path:

Phase 1: Suppress. Control. Hold back.

Phase 2: Adapt. Rethink. Collaborate.

Just as FEMA’s Risk Rating 2.0 moved toward personalized flood risk, wildfire policy is shifting toward localized, climate-aware strategies. Suppression alone is no longer enough. We need solutions that reflect today’s fire behavior — and tomorrow’s uncertainty.

The Dragon Bravo Fire is a signal: when planning lags behind conditions, the cost is cultural, ecological, and human.

Where Do We Go From Here?

One question to consider: How is your city preparing for wildfire? Are fire-adapted codes, defensible space, and seasonal planning part of the strategy?

We can:

Integrate fire into land use planning, as we do with floodplains — aiming to make communities reasonably safe from wildfires, just as FEMA aims to make them reasonably safe from flooding.

See forests not just as scenery, but as part of our water infrastructure.

Update emergency response based on current drought and wind conditions.

Elevate Tribal knowledge and leadership — not as symbolic gestures, but as co-leaders.

Promote reforestation with native, drought-adapted species. Ponderosa pines, for example, can survive on as little as 10 to 11 inches of annual rainfall — making them a natural fit for arid western landscapes.

If the Southwest is to thrive, it will need rooted, place-based resilience — drawing from both modern science and the longstanding practices of Native American communities who lived in balance with fire and drought. As George Santayana warned, those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

Geography isn’t the enemy. Like Lee Kuan Yew showed in Singapore, it can become our greatest advantage — if we plan with discipline and vision

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. This blog aims to educate and empower readers through objective geographic and planning insights, fostering informed discussion on global and regional issues.