Why are local taxes so high

It's not just the tax rate. State mandates, planning promises, and a city's economic base quietly shape what residents end up paying

If you’ve ever compared your property tax bill with a friend in the next town and asked, “Why are mine higher?” you’re asking a fair question. But it often leads to frustration, not understanding.

A better question is simpler:

What am I paying for?

I think about local taxes as a three-legged stool.

One leg is state and federal mandates — the costs cities are required to cover just to operate. Another leg is the local economic base — how much taxable activity exists to spread those costs across residents and businesses. The third leg is community choices — the services, standards, and long-term policies set through local planning and regulation.

Your tax bill isn’t random. It’s the price of those three forces working together, shaping the services you receive, the quality of life you expect, and the kind of community you want to live in.

To make smarter choices about our shared future, I believe it helps to understand how that stool is built — and what happens when one leg carries more weight than the others.

The “Have-To-Dos”: State & Federal Mandates

Every city begins with a set of non-negotiable obligations set by state and federal law. Courts, public safety, health standards, and certain education requirements aren’t optional. They’re the price of being a municipality.

Even in states with strong home rule authority, local governments operate within boundaries defined by higher levels of government. In states that follow Dillon’s Rule, those boundaries are even tighter.

The key point is this: these mandates come first. They set the floor. Before a city makes a single local choice, a significant share of its revenue is already committed.

That’s why I don’t start by blaming city council when people look at a tax bill. Much of what residents pay for isn’t the result of local preference or political ideology. It’s part of the landscape — like climate or underlying geology. Real local control begins only after these obligations are met.

The “Raw Power” of Your Place: The Local Economic Base

This is where geography quietly shapes your tax bill.

Some places start with enormous advantages. A landlocked town with poor soils and no navigable river starts with a very different hand than a coastal port. Those differences don’t just shape how places grow — they shape the fiscal reality cities live with every day.

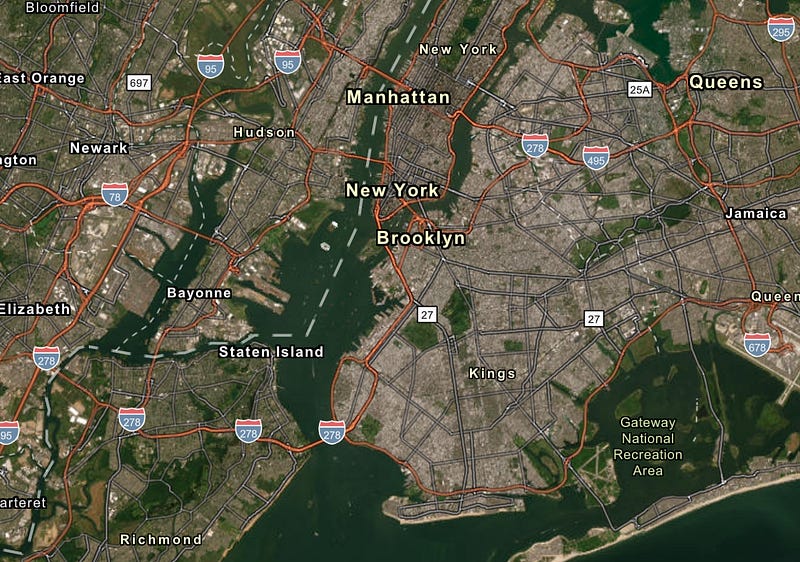

New York City is a clear example of what I think of as super geography. Sitting at the mouth of the Hudson River — one of the most navigable rivers in North America — and paired with one of the world’s best natural harbors, New York began with a powerful edge. Goods, people, and capital could move more easily there than almost anywhere else. Over time, that advantage translated into economic dominance, global influence, and extraordinary fiscal capacity.

That kind of raw power matters — and it isn’t evenly distributed. Geography is not egalitarian. Some places are simply blessed with more advantages than others. Planning as if that difference doesn’t matter is a recipe for financial stress.

Economists have reached a similar conclusion from another angle. In Triumph of the City, Edward Glaeser shows that cities grow stronger when they concentrate people, jobs, and ideas — creating what he describes as creative collision. Places with a healthy mix of homes, offices, shops, and industry can spread the cost of public services across a broad base. Bedroom communities with little commercial activity cannot. In those places, residents shoulder most of the burden, and tax rates feel higher even when services are modest.

This is why copying the policies of a powerful city can backfire. New York can afford big promises because its geography and economy support them. Most cities cannot.

Geography sets the starting point — not the destiny. What ultimately matters is how a place aligns its geography with its human capital.

The “Choose-To-Dos”: Your Community’s Vision & Promises

This is where local control truly exists.

Every city adopts a Comprehensive Plan — its official blueprint for the future. I unpack what these plans are and why they matter in more detail in What Is a Comprehensive Plan — and Why It Matters). Embedded in that plan are Level of Service standards: measurable promises about roads, parks, fire response times, and public facilities. What’s often missed is that these promises are supposed to be paid for through the Capital Improvements Plan, which lays out how — and whether — the community will fund those commitments over time.

In other words, a plan isn’t just about what a city wants. It’s about whether those wants fit its geography, its economic base, and its capacity to pay.

Alain Bertaud, in Order Without Design, makes this point more bluntly: planning is ultimately about resource allocation, whether planners acknowledge it or not. Land-use rules and Comprehensive Plan policies shape land prices, commuting distances, transportation costs, and where jobs and housing can realistically locate.

Those choices become real through design. A twelve-foot travel lane costs more to build and more to maintain than a narrower one. Sprawling street networks require more pavement, more pipes, and more long-term upkeep than compact ones. Many of these decisions are treated as technical standards, but they are also long-term financial commitments that compound year after year. As urban economist Edward Glaeser has observed, land use controls have more widespread impact on the lives of ordinary Americans than almost any other regulation.

Cities often look to impact fees to help close the gap. These fees are meant to ensure that new development pays its fair share for the infrastructure it requires. But impact fees are not a blank check. They must be tied to a clear, defensible connection between a development’s impacts and the public costs imposed. Courts have repeatedly reinforced this principle, most recently in Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, which reaffirmed that governments cannot simply shift the cost of ambitious plans onto developers without meeting strict legal standards.

This is where daily life meets your tax bill. It’s also where a hard truth emerges. As Thomas Sowell observed in Basic Economics, “The first lesson of economics is scarcity.” Resources are limited. Promises are not. A city can plan for almost anything on paper — but it still has to pay for what it builds, maintains, and eventually replaces.

This is why sprawl matters so much to local finances. When development spreads out faster than a city’s economic base grows, the cost of serving that pattern eventually shows up — in higher taxes, deferred maintenance, or declining service levels. A Comprehensive Plan is not just a vision document. It is a financial document written in policy language, and its success depends on whether promises, design, and funding are aligned.

The Bigger Picture

Comparing tax rates between towns is usually misleading. It ignores the system behind the number. A city with lower taxes may offer fewer services, benefit from an unusually strong economic base, or defer maintenance — quietly shifting costs to the future.

It’s also important to recognize that states raise revenue in different ways. Some rely more on income taxes, others on sales taxes, and others — like Florida — lean more heavily on property taxes. One way or another, public services still have to be paid for. The difference is where the bill shows up.

The truth is simple but uncomfortable: higher service levels cost more. When a community promises more than its economic base can sustain, the bill eventually comes due — through higher taxes, declining services, or both.

The goal isn’t cynicism. It’s honesty. Resilient communities align their vision with their wallet.

If you want to understand your own tax bill, start with your city’s Comprehensive Plan and look for “Level of Service.” Those policies spell out what your community has already promised. Then ask the harder question: do those promises fit the city’s economic strength, or are they setting up future tax shocks and deferred maintenance?

The best plan isn’t the most ambitious one. It’s the one that can be paid for — year after year. As Charles Marohn often argues, financially resilient cities grow incrementally, through small, adaptable investments that deliver real economic return. When that balance breaks down, people respond. As Edward Glaeser has shown, they vote with their feet — moving to places where taxes, services, and opportunity make more sense. That movement is the most unforgiving tax policy of all.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. It empowers readers with objective geographic and planning insights to encourage informed discussion on global and regional issues.