Why Do We Still Build in the Floodplain?

Why do we keep building in floodplains? Explore outdated maps, weak policies, and real-world risks—and how smarter planning can save lives.

Introduction: Why This Matters

Why Do We Keep Building in Floodplains? After every major flood — from Hurricane Helene to the tragic Camp Mystic flash flood in Texas — the same question arises: Why are we still building in known floodplains?

As a Certified Floodplain Manager and Certified Urban Planner, I hear this often. This isn’t just an academic debate. It’s about safety, resilience, and the rising costs of disasters — especially as climate change fuels more extreme weather events.

In 2024, Hurricane Milton proved it again. Catastrophic inland flooding swamped neighborhoods far from the coast — areas once deemed “low-risk.” Record rainfall turned roads into rivers, trapping families and destroying homes that often lacked flood insurance simply because the maps said they didn’t need it.

The Background: A Policy That Changed the Landscape

To understand how we got here, we need to go back to 1968 — the year Congress created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). At the time, flood losses were mounting, and private insurers had largely pulled out of the market. The NFIP was a bold experiment: in exchange for federally backed flood insurance, communities agreed to adopt basic land-use rules to reduce future risk.

It was an important step — but not a perfect one.

Many homes and businesses were already in flood-prone areas before the first flood maps existed. These “pre-FIRM” structures were grandfathered in. Even today, federal rules under 44 CFR §60.3 set only minimum development standards, and local governments often choose not to exceed them.

To be clear, FEMA and its partners work hard to manage flood risk accross the country. With limited funding, increasing development pressure, and changing climate patterns, their job is increasingly complex. Still, as flood risk evolves, it may be time to re-evaluate how we support FEMA’s efforts — particularly in modernizing flood maps, strengthening local partnerships, and helping communities move beyond minimum compliance.

Why It Still Happens: A Web of Factors

So why does this continue? A number of overlapping factors help explain the ongoing pattern of development in high-risk areas:

Outdated or incomplete flood maps (such as FEMA Zone A areas) give a false sense of security.

Section 60.3 of 44 CFR allows floodplain development if it meets basic elevation and permitting standards — but local enforcement and capacity vary widely.

Concerns about private property rights can make it politically or legally difficult to restrict development, especially in rural or unincorporated areas.

Local zoning laws may not align with updated flood risk — or lack political support for stricter floodplain protections.

Waterfront properties continue to be desirable and profitable, regardless of flood risk.

NFIP insurance subsidies may reduce the perceived cost of building in high-risk areas.

New development — including roads, homes, and parking lots — can alter how and where floodwaters flow, intensifying downstream impacts.

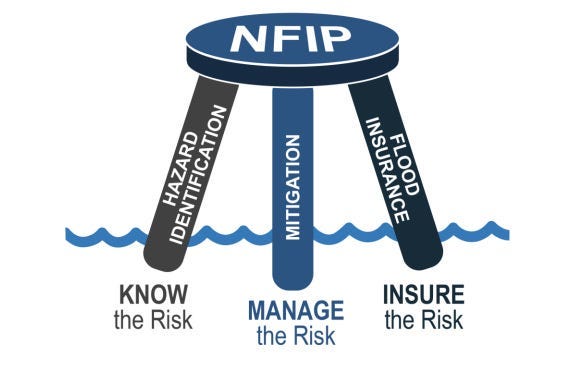

The NFIP is like a three-legged stool, relying on accurate maps, affordable insurance, and strong regulations. Outdated maps or lax rules make it wobbly, risking lives and property

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is like a three-legged stool: it depends on accurate maps, affordable insurance, and strong local regulations. If one leg is weak — especially outdated maps or lax enforcement — the whole system becomes unstable.

What Flood Maps Do — and Don’t — Tell You

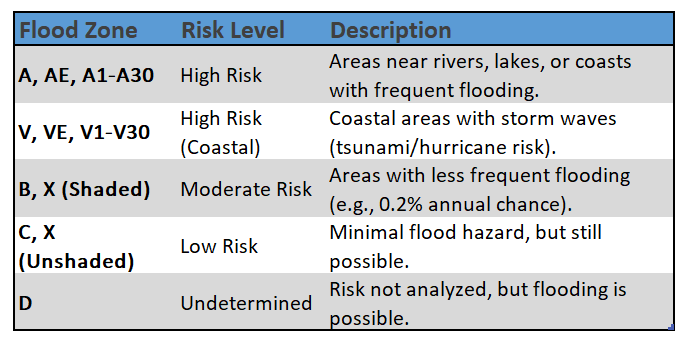

FEMA’s Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) are essential tools for identifying flood risk — but they’re often misunderstood and not always complete.

One of the most commonly misunderstood areas on FEMA flood maps is Zone A — a high-risk flood zone with at least a 1% annual chance of flooding, commonly known as the 100-year floodplain. Unlike Zones AE or VE, Zone A lacks detailed engineering studies and does not include Base Flood Elevations (BFEs), making it harder to guide safe development. In many cases, the mapped floodplain boundaries in Zone A even cross contour lines, a sign that they’re based on approximate methods rather than ground-level modeling.

This matters because:

Without a BFE, it’s harder to know how deep floodwaters could get — or how high buildings should be elevated.

These areas often appear in rural or less-studied areas, relying on limited data.

Local governments or property owners must determine the BFE through additional site-specific analysis.

Despite the limited data, Zone A is still a high-risk area — and that lack of clarity can lead to unsafe new developments.

Regulatory floodways, which are also mapped by FEMA, represent the highest hazard areas within the floodplain. These corridors carry the fastest-moving water during a flood and pose extreme threats to life and property. Development in floodways is strictly regulated for good reason — but nearby development can still be vulnerable.

A Real-World Example: Camp Mystic

The tragedy at Camp Mystic in Kerr County, Texas shows how these mapping limitations can lead to loss of life. A portion of the site lies in Zone AE and even within the regulatory floodway, where development should be highly restricted. Yet other parts of the camp — still in Zone A — were developed under assumptions of lower risk.

The 2016 and 2024 aerial images below highlight how new construction extended into and near the Zone A floodplain, despite its high-risk designation.

When extreme rainfall overwhelmed the Guadalupe River, flash floods rushed through the site, inundating sleeping cabins and tragically taking lives. The camp lacked a real-time warning system, and the regulatory framework didn’t reflect the on-the-ground risk.

Camp Mystic is not just a local tragedy — it’s a national wake-up call. It shows what can happen when outdated maps, minimal regulatory standards, and limited public awareness collide with a powerful flood event.

Know Your Risk — and Your Tools

If you’re a property owner, renter, or local official, you can take steps today:

Look up your address on the FEMA Flood Map Service Center.

Understand your zone: Zones A, AE, AH, AO, V, and VE are considered high risk.

Remember: A 1% annual chance of flooding means a 1 in 4 chance over a 30-year mortgage.

But remember — maps are only the starting point. Many rely on historic rainfall and past land use, not today’s climate or development patterns. Urban growth, changing storm intensity, and altered watersheds are reshaping flood behavior faster than many maps reflect.

This is where better planning matters — not just for compliance, but for long-term safety and resilience.

The Takeaway: It’s Not Just a Map — It’s a Mindset

Flood maps are tools — but they’re only as good as the policies and decisions that guide their use. The real challenge lies in how we manage the tension between public safety and private property rights. Too often, development is allowed simply because it meets the minimum technical requirements — not because it’s safe, wise, or sustainable.

Camp Mystic is a painful reminder of what happens when the illusion of low risk meets the reality of flash flooding. And Hurricane Milton shows how flood disasters don’t just happen on the coast — they unfold inland, in parking lots, backyards, and main streets. These events highlight the need to rethink where and how we build — and how we warn.

But maps don’t always tell the full story. Longtime residents often carry valuable historical knowledge — memories of past floods, washed-out roads, or high-water marks — that aren’t reflected on official maps. Ignoring those insights can lead to decisions that overlook real risk.

Flood risk is not static. Our policies shouldn’t be either.

Call to Action: Build Smarter, Not Just Higher

Flood resilience requires more than federal compliance checklists. It requires communities and professionals to think critically and plan intentionally. If you’re buying a home in Florida, don’t let flood risk catch you off guard —Buying a Home in Florida? Don’t Overlook Flood Risk offers a step-by-step guide to reading FEMA maps, talking with local officials, and making safer decisions.

We need stronger local ordinances, better communication with the public, and the courage to prioritize long-term safety over short-term gain. That means balancing property rights with community resilience — and making decisions based on where water will go, not just where the map says it went last time.

If we keep building on outdated assumptions, we’ll keep repeating the same mistakes.

But if we plan smarter today, we can protect more lives tomorrow.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. This blog aims to educate and empower readers through objective geographic and planning insights, fostering informed discussion on global and regional issues.