Why Singapore Is Rich: The Alignment Blueprint That Drove Its Economic Miracle

How geography, culture, and leadership worked together to produce extraordinary results.

For most of human history, the answer appeared straightforward: geography. Cities located on navigable rivers, natural harbors, or major trade routes flourished. Those without them struggled. Where you were largely determined what you could become. But in the modern world, that explanation is no longer sufficient.

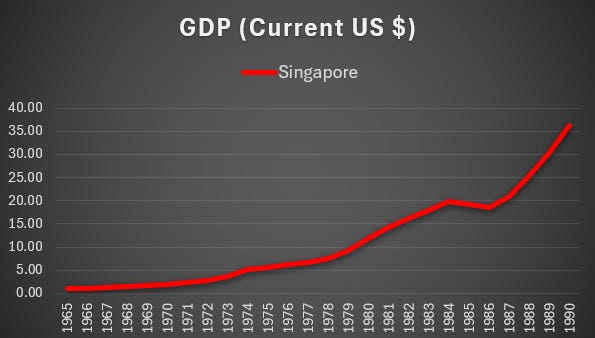

Singapore was once one of the world’s poorest nations. At independence in 1965, its GDP stood at a precarious $0.97 billion, and its survival was an open question. In 1965, a family in Singapore worried about their next meal, not stock markets. Just one generation later, by 1990, that figure had grown to over $36 billion. This wasn’t just growth — it was a metamorphosis.

As Alexander Hamilton observed, national wealth springs from “an infinite variety of causes.” Improving any single factor can move a place forward. But Singapore’s rise suggests something more powerful: extraordinary transformations occur when those forces are deliberately aligned.

In Singapore’s case, that alignment came from three elements working in concert: Geography, Culture, and Leadership.

Geography: Leverage Geography

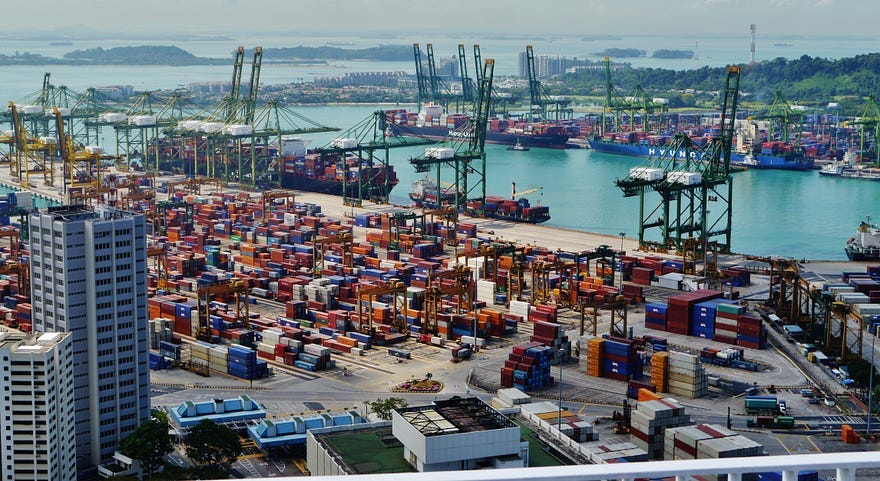

Singapore began with no freshwater, no farmland, and less land than Orlando metropolitan area. But it had one colossal asset: a natural deep-water harbor — where the world’s largest ships could dock — sitting on the Strait of Malacca, a global trade artery. This was a gift. A deep harbor can be built, but that requires immense capital — something Singapore utterly lacked. A natural one is a foundation laid by geology.

Where others saw a swamp, he saw a strategic stage. The choice was clear: stop resisting geography, and and build on it.

Geography was Singapore’s starting point — not its destiny. I’ve explored how Lee Kuan Yew turned the island’s geographic constraints into strategic power in more detail elsewhere; here, the focus is on how geography only became transformative once culture and leadership aligned with it.

Culture: Crafting Homegrown human Capital

In 1965, Singapore was deeply diverse and tense. Most people were uneducated, and many couldn’t read. The solution was to forge a new culture through education — one engineered for its geography.

As economist Thomas Sowell defines it, culture include not only customs, values and attitude, but also skills and talent that directly affect economics outcomes, and which economics call human capital

A hub on the world’s busiest trade route needed engineers, technicians, and managers. So, it built a school system to produce them. But it did more than graduate individuals; it clustered this new talent in focused industries and research parks. It understood a fundamental urban truth: talent attracts talent, and density sparks creative collision. This investment in homegrown human capital didn’t just build a workforce; it overcame the original limits of geography itself.

Leadership: A Fair leader with transparent laws

Democracy and rule of law matters, but Singapore’s lesson is that the quality of rules and the nature of government matters more. Lee Kuan Yew understood that the real engine for transformation requires that the rules are clear, effort is rewarded, and tomorrow is predictable. Singapore’s leadership built institutions to provide that guarantee. It meant a ruthless, successful fight against corruption and courts that enforced contracts without favor. This created a reputation for exceptional government effectiveness. This wasn’t just administration; it was designing a nation’s victory in advance by building trust. This principle extended to the ultimate test of leadership: knowing when to step aside and let the system endure, a lesson Lee Kuan Yew himself mastered. It provided the steady hand that allowed geography and culture to work.

Leadership completed the alignment. Lee Kuan Yew understood that building a nation meant building institutions that could function without him — including the discipline to step aside once the system was strong enough. I’ve explored this idea more deeply through historical parallels, from ancient Rome to modern Singapore; here, it matters because leadership continuity allowed geography and culture to compound over time.

Conclusion

So why do some places thrive while others fall apart?

Geography still matters — but it no longer decides the outcome on its own. In today’s world, prosperity emerges when geography, culture and leadership reinforce one another over time. Alignment turns constraints into strategy and opportunity into endurance.

Singapore didn’t defy geography. It mastered it — by aligning its physical limits with human capital and leadership capable of thinking beyond the next election or business cycle.

That is the real lesson. Not to copy Singapore, but to understand your own place well enough to align its geography, culture, and governance toward a shared future. In the modern era, success belongs not to places with perfect conditions, but to those that learn how their system fits together — and act accordingly.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. It empowers readers with objective geographic and planning insights to encourage informed discussion on global and regional issues.