Fighting Fire with Trees and Native American Wisdom

How Native American prescribed fire and fire-adapted and drought-resilient trees can reduce wildfire risks and support ecosystem recovery.

Fire in a Changing West

Wildfires in the American West are burning hotter, longer, and with greater destruction than generations ago. Nearly a century of fire suppression has created dense, flammable forests, while drought and rising heat compound the risk. Recent events such as the Gifford Fire in California and the Dragon Bravo Fire in the Grand Canyon show how steep slopes, rugged ridges, and dry vegetation make suppression especially challenging. In such terrain, understanding topography is as important as firefighting equipment when planning safe, effective strategies. Yet the solution may not rest solely in more bulldozers, watchtowers, or even advanced AI — it may lie in ancient practices that worked with the land instead of against it.

For thousands of years, Native Americans used fire to shape resilient, diverse landscapes. According to The Tribal Wildfire Resource Guide, this “Indian-type fire,” a form of intensive land management in which areas are treated in a variety of ways over time to create a mosaic of forests and grasslands, rather than uniform monocultures. The result is a diverse landscape of open prairie or savanna, shrubland, young trees, mature stands, and old-growth forest. These patterns reduced the likelihood of catastrophic wildfire while sustaining cultural resources. Organizations like Wildfire Risk to Communities note that Indigenous-led fire stewardship remains a vital tool today, blending cultural tradition with modern fire science.

Elevation shapes fire as much as climate does. Riding the gondola up Sandia Peak overlooking Albuquerque, New Mexico, you can watch the landscape change in real time — from the dry, pinyon–juniper woodlands of the lower slopes, to the fire-adapted ponderosa pine belt, and finally into the cooler, denser mixed conifer forests near the summit. Each zone has its own rhythm of fire and recovery, and Indigenous fire stewardship adapted to these differences. The higher you climb, the less frequent the fires, but when they do come, they tend to burn hotter and over larger areas.

The Majestic Ponderosa Pines

Many drought-hardy species are also naturally adapted to survive — and even benefit from — fire. Ponderosa pine, with its thick bark, can withstand low-intensity burns. Shortleaf pine can resprout from its base after fire. Some trees, like lodgepole pine and giant sequoia, even require fire’s heat to release their seeds. Beneath the ponderosa pines of northern Arizona, the Milky Way arches overhead — a reminder that these time-tested survivors share the same land and sky that sustain us. Such resilience is no accident. Many Native traditions deliberately maintained forests like these through regular, controlled burns.

Traditional Fire: Purpose and Practice

In many regions, tribes burned every few years to create a patchwork of habitats, which boosted biodiversity and kept fuel loads low. Fire was a tool for hunting, agriculture, pest control, range management, and water stewardship. These burns were not destructive acts, but deliberate interventions that balanced ecological health with cultural needs.

Modern ecological science confirms these benefits. Low-intensity prescribed burns reduce hazardous fuels, stimulate growth of fire-adapted plants, and improve soil health. The parallels between these traditional practices and today’s resilience goals are striking.

Restoring the Balance: Trees as Living Infrastructure

When paired with the right tree species, cultural burning becomes part of a larger system of green infrastructure. Trees like ponderosa pine, shortleaf pine, lodgepole pine, giant sequoia, and pinyon pine have evolved to thrive in fire-prone, often drought-stressed landscapes.

Mass plantings of native, drought-hardy species can stabilize soils, shade the land, and capture scarce rainfall. Combined with seasonal burns, these plantings create landscapes that are both fire-resilient and water-wise.

A Lost Partnership Between People and the Land

What if the Western wildfire crisis is not just the result of climate change and a century of suppression, but also an unintended consequence of disrupting a special ecosystem — one where people and land worked in harmony? For millennia, Native Americans practiced cultural burning that kept fuel loads in check, nurtured fire-adapted trees like the ponderosa and giant sequoia and created patchwork landscapes rich in biodiversity. These burns were not random; they followed the natural rhythm of the seasons and the needs of the land. When Indigenous peoples were forced from their homelands and these practices were outlawed, that rhythm was broken. Without the regular, low-intensity fires that maintained balance, fuels accumulated, forests grew denser, and today’s megafires found the conditions they needed to thrive.

Fire, Forests, and Water: A Linked System

The Dragon Bravo Fire on the Grand Canyon’s North Rim showed how wildfire can threaten more than forests — it can endanger water supplies. The North Rim is part of the Colorado River watershed, which sustains 40 million people according to the United States Bureau of Reclamation (USBR). A burned forest canopy can reduce snowpack retention and allow ash to contaminate downstream water.

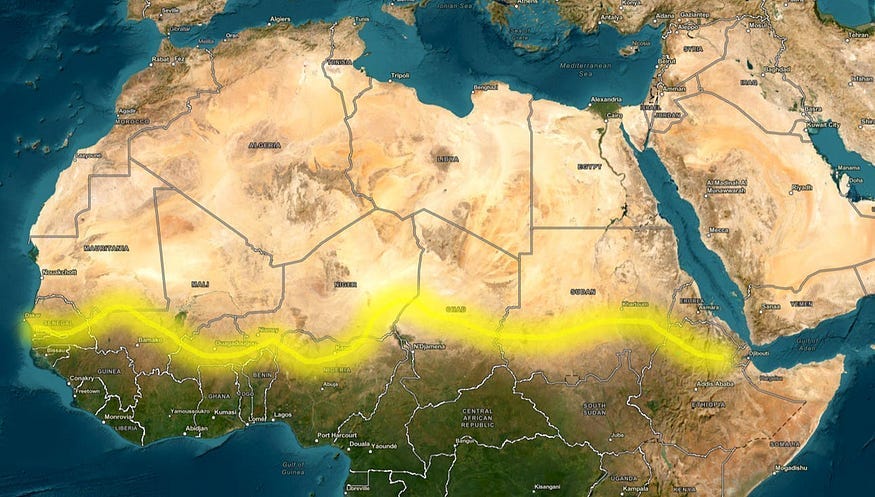

Lessons from the Great Green Wall

According to the Great Green Wall Initiative, the project demonstrates the power of combining local ecological knowledge with strategic planting to restore degraded landscapes and build resilience. In the U.S. West, similar lessons apply: Indigenous-led fire stewardship and native tree restoration show how cultural knowledge can strengthen resilience. The Tribal Wildfire Resource Guide handbook emphasizes that fire can enhance fire-resiliency, protect cultural resources, and even create economic opportunities through biomass utilization.

From Suppression to Stewardship

Fire policy is shifting from a century of suppression toward a more balanced approach — much like floodplain management evolved from pure levee-building to integrated zoning and open space preservation. The Tribal Wildfire Resource Guide handbook notes that prescribed burning, fuel reduction, and Indigenous fire stewardship are now recognized as essential to long-term forest health.

How You Can Support This Shift

Ask yourself: How is your community planning for wildfire? Could cultural fire be part of your city’s toolkit, the way floodplain zoning is part of flood policy? Support Indigenous-led fire programs. Attend public prescribed burn demonstrations. Plant native, drought- and fire-adapted trees in appropriate locations. Advocate for fire-resilient land use and building codes. Resilience is not built in a season — it’s grown over time, rooted in both ancient wisdom and modern science.

Let’s work with nature — and ask ourselves: What will we bring back?

Some may see me as an extrovert, but I lean more toward introversion. My strength comes from being in nature — from the rugged mountains of the West to the magical natural springs of Florida. These places are where I feel grounded, renewed, and reminded of why the fight to preserve them matters. They are worth protecting not just for ourselves, but for generations to come.

There’s a serenity and peacefulness you can only experience beside water this pure — a place that feels like hallowed ground. This is the forgotten Florida, still alive for those willing to seek it out.

For more on these interconnected issues, see: Las Vegas and the Southwest’s Water Reckoning, How Africa’s Great Green Wall is Fighting Desertification, Beyond the Flames: The Dragon Bravo Fire, and the upcoming Fighting Drought with Trees.

“Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.” — Lao Tzu

The challenge now is to bring back that unhurried rhythm — to restore not only our forests, but also the knowledge and relationships that once kept them in balance.

Just as the return of wolves to Yellowstone restored balance to the park’s ecosystem, perhaps the return of Indigenous fire stewardship could help restore balance to the Southwest — reviving a partnership between people and land that once kept both healthy.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. This blog aims to educate and empower readers through objective geographic and planning insights, fostering informed discussion on global and regional issues.