Key Things to Know about the Garnet Fire

Steep terrain, beetle-killed forests, and drought stress are fueling California’s Garnet Fire — raising urgent questions about resilience and sequoia survival.

Sparked by lightning on August 24, the Garnet Fire in California’s Sierra Nevada is now testing firefighters in some of the steepest, driest terrain on the West Coast. Beyond acres burned or daily containment updates, the fire’s trajectory is being shaped by enduring geographic and ecological forces.

Here are key things to know that reveal why fires in the Sierra Nevada behave the way they do — and why they matter for the future. The urgency lies not only in protecting homes and infrastructure, but also in safeguarding giant sequoias — some more than 2,000 years old.

Here are Key Things to Know:

Rugged Granite Terrain

Look at this landscape. Imagine hauling heavy gear up steep granite slopes, cutting fire lines through smoke and heat. The fire is pushing north into rugged canyons where crews carry hoses, saws, and equipment through fields of dead timber. With few roads and little access, they rely on hand tools, dozers where possible, and portable water systems. Drainages like Dinkey Creek act as chimneys, pulling flames uphill and magnifying risks. Progress comes only through exhausting persistence in some of the hardest terrain imaginable.

Beetle-Killed Forests: Fragility and Fuel

Beetle-killed forests present a challenge for both ecology and wildfire safety. Decades of bark beetle outbreaks have transformed Sierra forests, leaving millions of dead pines standing like matchsticks. These “red and gray” trees dry quickly, fall unpredictably, and ignite with extreme intensity. Rather than slowing a fire, beetle-killed slopes act like accelerants, carrying flames into the canopy and showering embers downslope. For firefighters, each step through snag-heavy terrain is exhausting and dangerous — containment depends on navigating landscapes where the fuels are literally stacked against them.

Real-world modeling adds weight to what fire crews observe: a warming climate allows beetles to reproduce more quickly and survive through milder winters. In California’s Sierra Nevada, warming-enabled beetle outbreaks killed about 30% more ponderosa pines than drought alone Wildfire Today. A peer-reviewed study in Global Change Biology corroborates this, estimating that warming increased ponderosa pine die-off by roughly 29.9% during drought, largely due to more frequent beetle generations and higher survival rates.

Drought-Stressed Forests

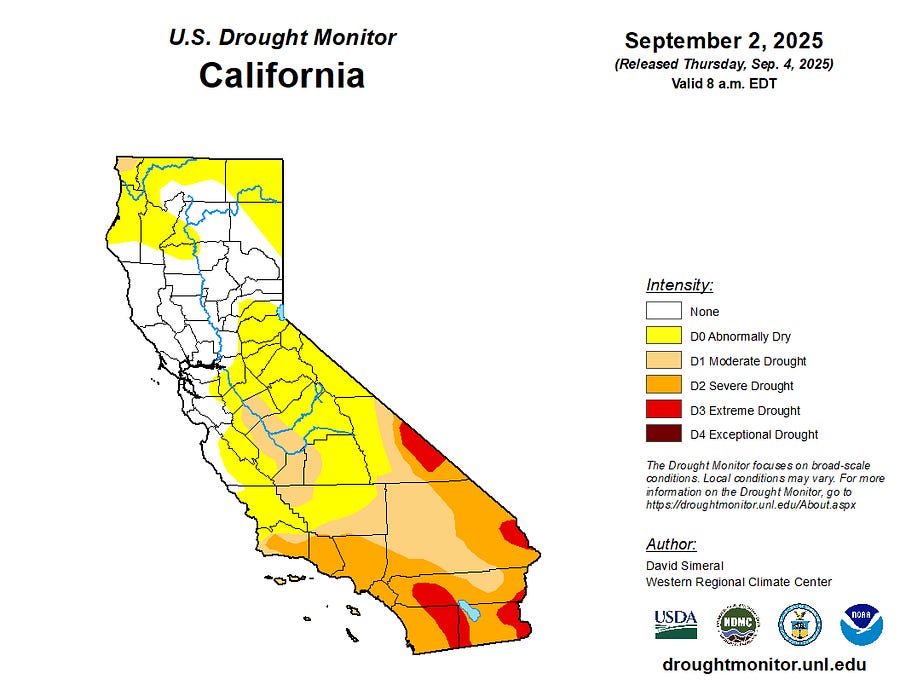

Drought is a sensitive subject, especially in California where it shapes lives, landscapes, and economies. The U.S. Drought Monitor shows Fresno County — the center of the Garnet Fire — under Abnormally Dry to Moderate Drought conditions.

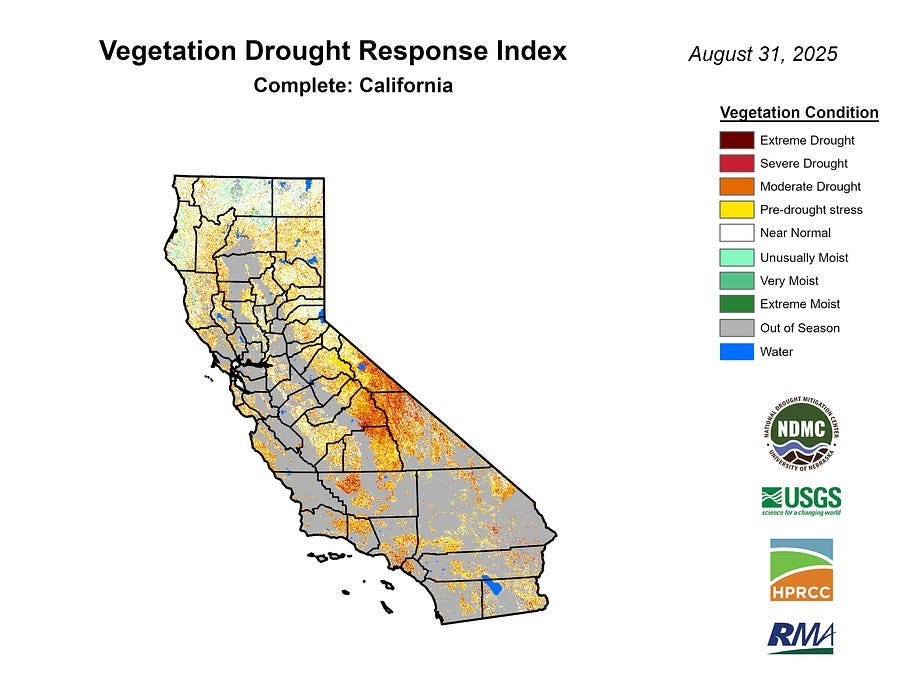

While broad indicators may show only “abnormally dry” conditions, vegetation on the ground frequently reveals deeper stress. Tools like the Vegetation Drought Response Index (VegDRI), which combines satellite and climate data, often detect moderate to severe vegetation stress even when hydrologic measures look modest. That lingering stress primes fuels to ignite faster, burn hotter, and even jump natural barriers like the Kings rivers, which often serve as firebreaks, may not hold when embers leap across.

Giant Sequoias: Fire-Adapted but Vulnerable

Crews are working to shield the McKinley Grove of giant sequoias — living monuments that rank among the largest and oldest beings on Earth. Some of these trees were already standing when Rome still ruled the Mediterranean. Their thick bark and towering canopies evolved with fire. For millennia, low-intensity burns cleared the understory, recycled nutrients, and opened cones for new generations.

But today’s megafires are different. A century of fire suppression, hotter droughts, and crowded forests mean flames now burn with unnatural force. Crown fires now climb into the sequoias themselves, killing giants once thought nearly immortal. Protecting them takes both emergency action — wrapping trunks, setting sprinklers, cutting fuel lines — and long-term foresight. Sequoias remain symbols of resilience, but they are also reminders of how altered landscapes can turn fire from friend into foe.

Sequoias are not the only species built to live with fire. Across the West, trees like ponderosa pine and pinyon pine share the same resilience, shaped by centuries of Indigenous fire stewardship. I explore these traditions and their lessons for today’s wildfire crisis in Fighting Fire with Trees and Native American Wisdom.

The Broader Implications

The Garnet Fire reveals how geography, climate, and ecology collide in the Sierra Nevada. Protecting communities and sequoias takes more than bravery in the field; it requires rethinking how we live with fire. For centuries, low-level burns sustained resilient forests. But decades of suppression, coupled with a hotter climate, have set the stage for today’s megafires.

Fire, drought, and water are inseparable in the American West. The Garnet Fire is one chapter in a larger story of how climate shapes survival — from the sequoias of the Sierra to the shrinking reservoirs of the Colorado River. For a deeper look at that connection, see Las Vegas and the Southwest’s Water Reckoning and The North Rim Grand Canyon: What It Reveals about Fire, Drought, and Resilience.

The critical question is whether the West will keep racing fire by fire, or begin reshaping its landscapes to work with fire as a natural force.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely my own and do not reflect those of any public agency, employer, or affiliated organization. It empowers readers with objective geographic and planning insights to encourage informed discussion on global and regional issues.